What a Squabble Within Academic Poetry Can Tell Us About Our Culture

The problems with populism

A few years ago, there was a STORM in the poetry world. Well, this is establishment poetry which is about as relevant to the public as saying there was an argument about Warhammer in Games Workshop, so when I say ‘poetry world’ I mean a poet wrote something criticising the poetry establishment in a poetry magazine hardly anyone reads, and by ‘storm’ I mean a few academics and poets responded with objections and pretty much no one else noticed.

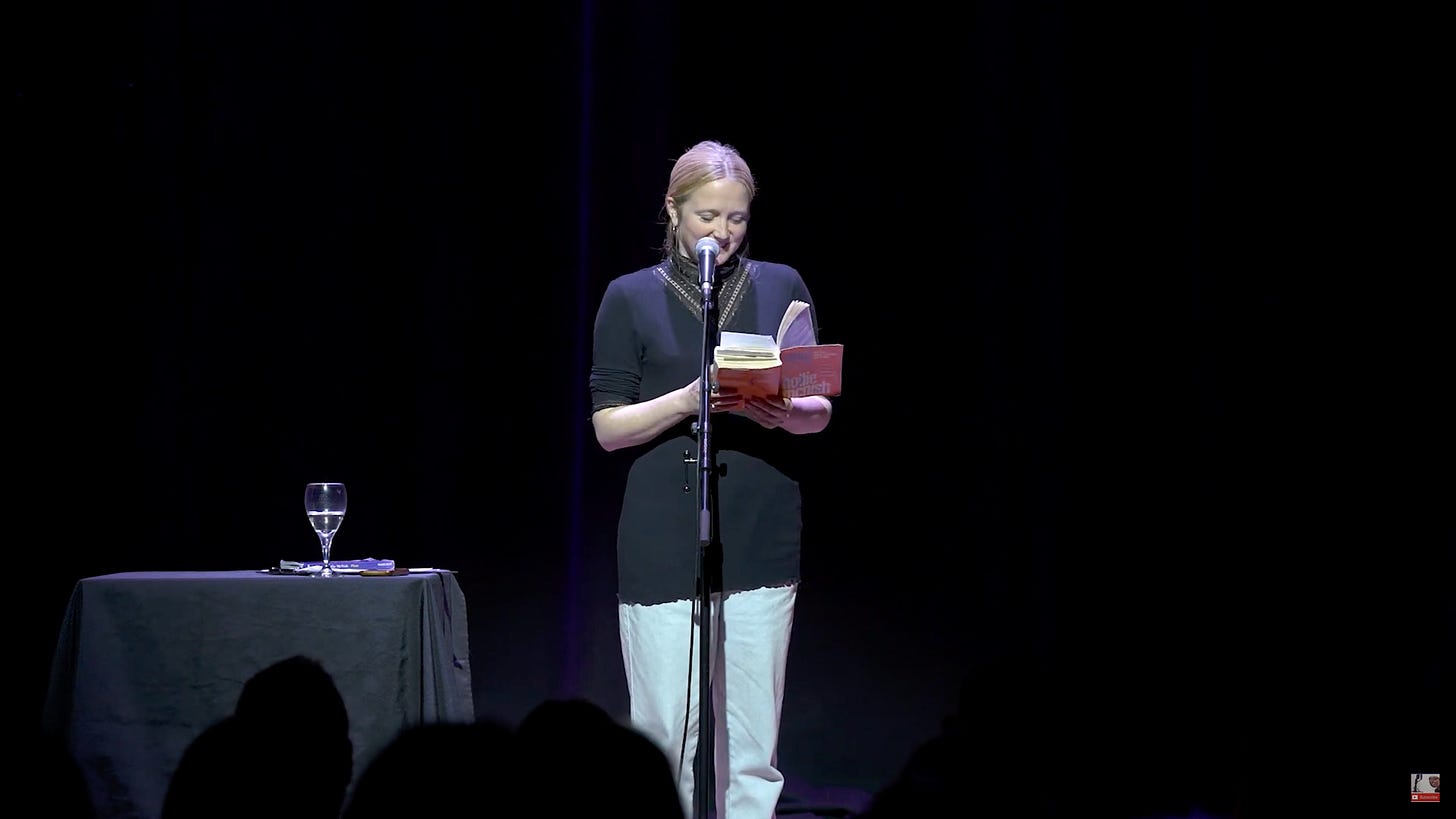

Yet for all its insignificance, this argument matters for the state of culture at large. The original article titled ‘The Cult of the Noble Amateur’ was written by a reasonably unknown poet named Rebecca Watts in Poetry Nation Review. Watts objected to a ‘cohort of young female poets’ who are being praised by the establishment, represented for Watts by a spoken word poet named Hollie McNish as well as others such as Kae Tempest, both of whom are edited and thus endorsed by respected poet Don Paterson, and both of whom have won significant establishment awards including the Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry.

Watts did not agree, she compared the popularity of McNish and co in the UK to that of instapoet Rupi Kaur, and referred to the work of these popular female poets as the “open denigration of intellectual engagement and rejection of craft.”1

While the debate seems superficially to be about whether you like a certain kind of popular ‘poetry’ or whether you find it nauseating, the questions cut a lot deeper. Poetry as an art form is one that up until the advent of instapoets had resisted mass commodification and thus the establishment did not exactly have to choose between what it values and what sells, but as Watts pointed out, with poets like Kaur suddenly poetry was making bigger profits than it ever had, and Watts viewed this as based on a simple discovery: “artless poetry sells.”

Yet this issue is not limited to poetry. Watts argues this results from a far bigger set of problems that extend from politics to culture to our own individual attention spans and is driven by the “dumbing effect” of social media with the result that for language driven art and its need to resist sound-bite and cliche “The reader is dead: long live consumer-driven content and the ‘instant gratification’ this affords.”

Watts describes the inevitable result of the popularising rather than the valuing of art as producing cults of personality:

What good is a flourishing poetry market, if what we read in poetry books renders us more confused, less appreciative of nuance, less able to engage with ideas, more indignant about the things that annoy us, and more resentful of others who appear to be different from us? The ability to draw a crowd, attract an audience or assemble a mob does not itself render a thing intrinsically good: witness Donald Trump. Like the new president, the new poets are products of a cult of personality, which demands from its heroes only that they be ‘honest’ and ‘accessible’, where honesty is defined as the constant expression of what one feels, and accessibility means the complete rejection of complexity, subtlety, eloquence and the aspiration to do anything well.

The selling point of a lot of these pop-poets then is not the artistic content they are producing but the popularity of the personality that produced them. What reviewers who praise them describe are not qualities of content but most particularly their “honesty” of expression, one reviewer said of McNish “It’s not that she doesn’t care about things like scansion and simile; more that, in her personal list of aesthetic priorities, immediacy and honesty matter more.”

What Watts goes on to point out is that honesty or authenticity are not necessarily artistic virtues, especially when it becomes primary to the ignoring and degrading of the craft itself. Poetry no longer is a “deliberately created work” or an “art form” and thus part of these poet’s popularity stems from the same reasons as the success of political populists in the age of social media: their effect is in being “unintimidating to anyone who considers ignorance a virtue.” McNish includes poems in her poetry collections written at ages throughout her childhood starting at 8, indicating that the improvement of craft is less important that the portrayal of the writer as a personality and Watts was amazed McNish openly admitted that her publishers sent her a pile of books to read because they felt she hadn’t read enough poetry. That latter point isn’t just an insult then, these poets really do consider ignorance part of their authenticity.

Yet this transition can hardly be said to be unique to poetry. In fact, the spoken word poets and the instapoets are in some ways stragglers in a phenomenon that now defines a huge part of our culture, that of the undiminishable accumulation of a following based solely upon personality and relying on the dynamics of social media and its algorithm assuring popularity for the sake of popularity at the expense of art. What Watts is trying to argue about what McNish is doing is said out loud by a generation trying to be “their authentic selves,” and is represented in a culture that clearly is absent of the separation between art and artist that gives cultural value to the work itself without us needing to know what the artist likes for breakfast or what they think about immigration policy.

The narrative of artist as authentic self artlessly narrativising their own existence is hardly separable from the culture the internet has come to create. What McNish is doing is basically the literary equivalent of vlogging, and the age of YouTube has generated a class of people who make a living doing literally just that. British YouTuber Zoe Sugg for example is now a multi-millionaire thanks to accumulating 10 million YouTube subscribers on one channel alone and 5 million on her “vlog” channel and is married to fellow YouTuber Alfie Deyes, also a millionaire YouTuber, and has two kids, which now feature in her vlogs (weirdly, since I’m not sure a child can consent to having their childhood broadcast on the internet). She has built her success literally filming herself talking to her friends, going shopping or opening her bags of clothes she’s bought. She now films her kids and has videos including things like “What’s In My Bag?” which has 3.3 million views where she literally just shows you what’s in her handbag.

We may mock this but every single Hollywood actor or pop star now does the same thing, so much so that the actual thing they do is basically secondary to the maintenance of their popularity by attending the abundance of celebrity crafted YouTube shows like Hot Ones, and partaking in a non stop cycle of parasocial culture. Put ‘Sabrina Carpenter’ into YouTube and you can watch her eat hot chicken wings, try snacks from different countries, eat more chicken wings in a chicken shop, show you her morning routine, get ready for the Oscars, give you a tour of her home, take a lie detector test, show you what’s in her bag, cook apple pie, and so on ad nauseam that I could probably carry on making this list for the rest of the day. What does any of this have to do with being an artist? Nothing, because being an artist doesn’t matter.

Forget poetry, these people and the abundance of YouTube shows that host them have tapped into what McNish and co are doing without even having to pretend their artlessness is sufficiently authentic to be praised by any form of establishment. YouTube and social media mean anyone can cultivate a following based on pure voyeurism and personality cult, so much so that the churn of celebrity culture has boomed rather than decreasing. As much as we take something like Hot Ones to be banal and harmless, it represents a culture looking for mindless entertainment based on personality and faux-authenticity that masks a desperate narcissism at the behest of the value of art, creativity, craft or cultural value.

These may seem like banal complaints, but Watts points out that the sheer tidal wave of popularity means establishments that may have upheld what we once called art are faced with a tension between capitulating to popularity or diminishing into obscurity. For some establishments this means maintaining relevance by reaching for the representing of artist rather than art for reasons of category, a choice that some may refer to by the now puerile pejorative ‘woke’ but that Watts expresses much clearer:

The middle-aged, middle-class reviewing sector…is terrified of being seen to criticise the output of anyone it imagines is speaking on behalf of a group traditionally under-represented in the arts. Time and time again, the arts media subordinates the work — in many cases excellent and original work — in favour of focusing on its creator. Technical and intellectual accomplishments are as nothing compared with the ‘achievement’ of being considered representative of a group identity that the establishment can fetishise. This is reflected in headlines such as ‘Vietnamese refugee Ocean Vuong wins 2017 Forward Prize for Poetry’ (Telegraph), and phrases such as ‘oriental poise’ and the ‘ragged sleeve’ of ‘ordinary working people’ (Kate Kellaway in the Guardian, on Sarah Howe and William Letford respectively). Such attitudes are predicated on the stereotyping or caricaturing of ‘audiences’, rather than an appreciation of the existence of individual readers. Just as McNish insults those she expects to buy her books — condescending to an uneducated class with which she professes solidarity, while simultaneously rejecting her spoken-word roots — the critics and publishers who praise her for ‘telling it like it is’ debase us as readers by peddling writing of the poorest quality because they think this is all we deserve.

Hollywood and its accompanying media have tried this approach, but recently it seems have given in to the need for plain old popularity. Richard Hanania went viral last year for posting a clip of Sydney Sweeney on SNL with the tag ‘Wokeness is dead,’ and recently Sweeney’s much discussed jeans advert lead even the Guardian to point out that brands now care less about “woke-vertising” than they do about admitting the obvious fact that being blonde, white and having big boobs means you’ve got good genes and deserve to be popular. The recent complete brand failures of widely mocked figures like Brie Larson or Rachel Zegler seem to have brought the age of pretending to bandwagon certain moral fads into something embarrassing to the brand in favour of a more obvious acceptance that what is popular is popular.

In music this exchange has long gone. Streaming and pop charts have come to be dominated by an increasingly smaller number of artists with bigger audiences at the expensive of an ‘alternative’ within anything mainstream. Someone like Taylor Swift does what McNish does on steroids, writing songs that daisy-chain parasocial voyeurism into a cult of personality so spectacularly successful there are almost no sales or streaming records she doesn’t own. The fact that like McNish her lyrics are narcissistic and artless does not matter to critics who simply shrug and swing into discussing which song on her latest album is about which ex-boyfriend before awarding it five stars.

Yet it is not the mere presence of such figures that is the problem, as Watts points out, it is the establishment capitulation. I wrote an article several years ago titled “Why Taylor Swift is everything wrong with modern culture,” and my point then was not that Swift herself is the issue but instead the issues lies with the cultural establishment and reviewers who seemed unable to offer any kind of critique as to the shallowness of her entire dynamic in which she frames all criticism against her as a kind of anti-feminist takedown by her perceived enemies. God forbid they simply be people who give a shit about culture pointing out that a gazillion lazy metaphors for ex-boyfriends sold to fans looking for easter eggs is not art, and its sheer scale of popularity is a woeful indictment of the way the internet’s distribution dynamics have emptied a culture of artistic value.

Watts original complaint then was not just that certain poets have become famous for doing something that essentially parodies the idea of poetry or art itself, it was with the decline of literary criticism as having anything to say about what we mean when we talk about art. Watts is absolutely right, while certain art forms may easily capitulate to a commodification of the popular, when it comes to language the erosion of the way we value certain kinds of linguistic representation reflects something of a broader problem in self understanding. While we can’t expect any given time to present us with non-stop seminal works of art, and our review of the past has an inherent chronological bias that mines the seminal and forgets the banal in order to decry our own time, our very ability to understand what such a thing is and why it matters is fundamental to the possession of anything we can call a culture. This is not about snobbery but the resistance of inverse snobbery, rejection of the celebration of artless popularity and the celebritising of everyone in our culture. The modern West has volume to its credit, and perhaps we produce enough culture to redeem complaints about ‘decline’ that populate the conservative sphere, but with streaming and social media there is an increasingly exchange of volume for a loss of value.

This phenomenon is not even limited to artistic spheres like music, poetry or actors, but even to what we call ‘public intellectualism.’ Figures like Jordan Peterson and cohorts of other pop-academic figures who find mass fame and shift from academia to podcasting and professional talking reflect aspects of the same kind of cult of personality in which popularity means an inability to fail, a perpetuation of popularity on the basis of popularity. Nothing in online exchange is not suffering from the war for our threadbare attention spans and a race to the bottom that arrives inevitably at the absurd popularity of people like Bonnie Blue or Andrew Tate. YouTube channels like Jubilee are becoming centres of public discourse while at the same time degrading it by platforming extreme positions and bad spirit exchanges to absurdly high viewing numbers.

Whatever we can now call ‘we’ in our culture, ‘we’ seem to have no ability to plug this gap caused by the increasingly terrible incentives of the online world. Perhaps what Watts’ complaints reflect is the fact that ultimately establishments and critics simply don’t matter that much any more in a time where the selection and distribution of culture is not done by any kind of institution that might mediate value and profit as much as the indifferent selection of algorithms and their yoking to the lowest demands of our impulse. It turns out it’s not just the poetry establishment that has a problem.

This and subsequent quotes: Rebecca Watts, The Cult of the Noble Amatuer, PN Review 239, Volume 44 Number 3, January - February 2018.

This hit home as a twenty-something guy who has made a few unsuccessful attempts to get some poetry published over the years. I’ve found myself wracked with doubts over whether my work is just not any good or whether my style is just unfashionable at the moment. I think (or rather hope) it must be something in between. Obviously I have an awfully long way to go to perfect my craft, but I’m sure the fact that I loathe contemporary confessional poetry and try to be as unlike it as possible must be holding me back to some degree. Or maybe that’s just a cope. Whatever the case is, the current creative landscape looks extremely bleak and I’m not sure if there’s a future for me as a creative, but I haven’t given up quite yet.

Brilliantly assessed and stated.