The following is the first essay of a three part series on the affect theory of consciousness drawn from the free energy principle, and then a case for idealism. Part I attempts to explain the basic theory and principles so the subsequent arguments make sense, part II is on the philosophy and on consciousness itself and part III on how it all might relate to God.

All three articles will be available to all readers, parts II & III will be published Tuesday and Thursday respectively so please like/subscribe/restack or feel free to support my work with a paid subscription blah blah blah necessary self promotion over. I hope you find the essays useful.

*

Consciousness is nothing more or less than the activity of Maxwell’s daemon

Solms & Friston, 2018

*

Have you ever noticed that if you listen to a song enough times it doesn’t have that charge it had when you first listened to it, it becomes less alive with feeling and something that seems to easily fade into the background? Well, the free energy principle might in some convoluted way explain why. In fact, the free energy principle might just purport to explain why you feel anything about anything at all.

For some time, a minority of neuroscientists have believed that consciousness is rooted in and is affect, or feeling. Every conscious experience that you have is in some way valanced, in other words consciousness is not just what it is like to experience but what it feels like to experience. According to the neuroscientists who argue this, this is fundamentally what consciousness is.

If this is true, which at the very least it is to some degree, then we can explain what consciousness is doing by explaining what affect is doing. And now some neuroscientists are offering a simple answer: the purpose of affect is maintaining homeostasis in an organism by keeping its entropy low in accordance with the free energy principle.

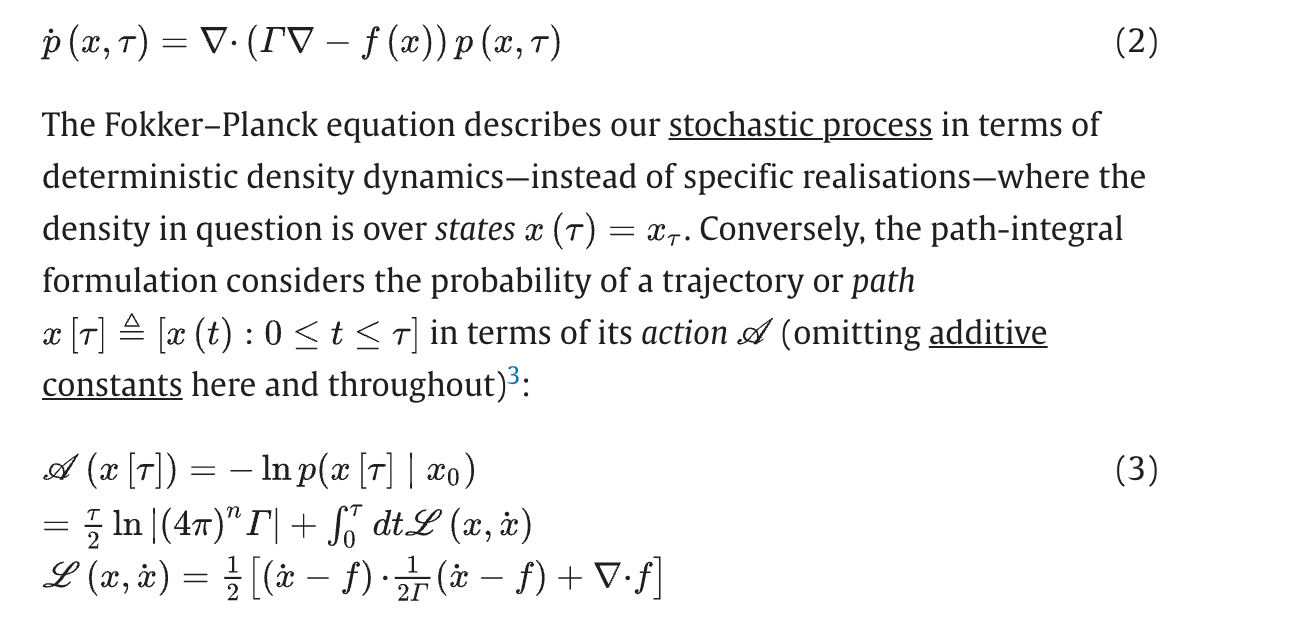

What is the free energy principle? Well, the answer is both incredibly simple and also indecipherably complicated. It is the product of Karl Friston, a revered neuroscientist, in fact the most cited in the field and one of the most cited living scientists full stop. Friston’s work however is notoriously difficult to decipher, for example in one paper in which he is supposedly making the free energy principle “simpler,” providing “a concise description of the free energy principle” and by using what he calls a “conversational style” to make it clear to readers, by one paragraph in the main text you are getting this:1

I’m not sure who this is conversational to except that it looks like what happens when you spill coffee on your calculator, and it seems like a paper designed to explain the concepts only to people who already understand them, and some far cleverer than me have pointed out that even to them his prose or tendency towards formulas not remotely explained to the uninitiated tend towards the impenetrable, something that has been mocked and parodied.2

Nonetheless, the basis of the free energy principle is pretty simple: Any organism3 has to survive by lowering its entropy, which means lowering its informational uncertainty. This means minimising the difference between the perceptual predictions of what is outside of the organism’s boundary4 and the information that enters into the system via sensory input. The amount of difference between the prediction of the world and the information about it is in simple terms what Friston calls free energy, although you can think about it even more simply as the need to minimise surprise.

The role of emotion, as Solms and Friston argue in their 2018 paper How and why consciousness arises, and as Solms argues in his book The Hidden Spring, is connected fundamentally to free energy. The maintenance of lower free energy is essentially about the maintenance of homeostasis, and the role of emotion is valence towards and away from this state of bodily equilibrium. Feelings are, if you like, the felt representation of the state of your free energy. They state at the start of their paper:

We will argue that the underlying function of consciousness is free energy minimization, and — in accordance with the above framework — we will argue that this function is realised in dual aspects: subjectively it is felt as affect (which enables feeling of perceptions and cognitions) and objectively it is seen as centrencephalic arousal (which enables selective modulation of postsynaptic gain)5

As it states at the start of this quote, they are not just making an argument for the role of emotion in minimising free energy but they are making the argument that consciousness itself is affect, or to put it more technically, emotional/feeling/affect is what arouses all of our conscious experience. In other words, sights, sounds, and so on are not forms of perception, but qualities of affect, aroused by the systems of the brain stem as part of the functional minimisation of free energy.

Affect then relates to homeostasis, and emotions reflect valence towards or away from the minimising of free energy by triggering prior predictive behaviours that are trained and retrained by the inferences from said predictive processes. Mark Solms expresses it simply as “decreases and increases in expected uncertainty are felt as pleasure and unpleasure, respectively…In short, consciousness is felt uncertainty.”6

What this means in part is that positive emotion is part of the stimulation not just of “foraging” behaviours that satiate negative affect but learning behaviours and ultimately the stimulation, in the long term, of thinking. Importantly though, consciousness itself and that which is made conscious is, again, about the increase and decrease of uncertainty. That which is familiar is already part of our predictive inference and so contains no information and so is not conscious. Consciousness, to re-word Solms, is what you don’t know. Consciousness, either positively or negatively, is novelty.

A trivial illustration of this might be floaters in your eye. You may at times notice a new floater as a dot or line in your vision, then after a while your brain tunes it out. This is not your brain realising it is a floater but rather according to ideas of the free energy principle, the objects themselves are so predictable that they contain zero information, and so they disappear.

How does this informational and thus quantitative property of a system become consciousness? Well, there is some neuroscience involved but first Solms argues that it emerges from the generation of complexity within biological systems in which organisms develop multiple homeostatic needs. I need to maintain the same body temperature, metabolise oxygen, get enough rest, get enough food, digest that food and so on. The difference within each of these systems in terms of self-monitoring, Solms argues, is quantitative, but the need to differentiate between different needs is qualitative. Solms puts it:

In other words, the requirement for compartmentalization becomes a necessity when the relative value of the different quantities changes over time. For example: hunger trumps fatigue up to a certain value, whereafter fatigue trumps hunger; or hunger trumps fatigue in certain circumstances, but not others (i.e., 10 × X is currently [but not always] worth more than 10 × Y). Such changes require the system not only to compartmentalize its work efforts in relation to its different needs, but also to prioritize them over time.7

This generates the need to make executive choices in unpredictable circumstances. We make these choices primordially, according to Solms, through feeling:

But how does the organism choose between X and Y when the consequences of the choice are unpredictable? The physiological considerations discussed in the previous section suggest that it does so by feeling its way through the problem, where the direction of feeling (pleasure vs. unpleasure) — in the relevant modality — predicts the direction of expected uncertainty (decreasing vs. increasing) — within that modality8

There are ways in which this is demonstrably true. Despite modern rationalism’s claim that we think our way through the world rather than feeling our way through it, there is evidence to the contrary. One example is cases of those who biologically do not experience fear. The idea that we should be fearless is a tired platitude, but as it turns out being fearless is a precarious state of existence. Solms sites an example of a patient who had a condition that resulted in the calcification of her amygdala and resultantly didn’t feel any fear:

She had been the victims of numerous acts of crime and traumatic life-threatening encounters. She has been held up at both knifepoint and gunpoint, was almost killed in a domestic violence incident, and has received explicit death threats on numerous occasions…the disproportionate number of traumatic events in her life has been attributed to a marked impairment on her part of detecting looming threats in her environment and learning to steer clear of potentially dangerous situations.9

So feeling guides us through the world. Solms argues that feelings themselves are generated in the same part of the brain stem that arouses us to wakefulness, and so feelings are fundamentally states or conditions of arousal that prioritise actions and behaviours aimed, simplistically, at lowering our predictive uncertainty. These states of feeling are what consciousness is.

Solms and Friston go further than consciousness though, arguing that the free energy principle gives the basis for selfhood, agency and intentionality. Because the free energy principle states that any thing that exists must maintain a boundary between itself and the external world, its own internal state must model the external world and must be internally monitored in order to continue to exist:

The fact that self-organizing systems must monitor their own internal states in order to persist (that is, to exist, to survive) is precisely what brings active forms of subjectivity about. The very notion of selfhood is justified by this existential imperative. It is the origin and purpose of mind.

Selfhood is impossible unless a self-organizing system monitors its internal state in relation to not-self dissipative forces. The self can only exist in contradistinction to the not-self.10

As I will get to, there are some circular definitions involved in the premises of the free energy principle, but the basic point is that internal self-monitoring is a basic feature of any negentropic (resistant to entropy) system with a boundary between it and the environment. This self monitoring and subsequent predictive response, according to this argument, already constitutes subjectivity, agency and intentionality and is the basis of the problem of other minds. Again, to put it as simply as possible: according to the FEP any system with a boundary must self monitor its internal state and calibrate its relation to inferences about the environment, which constitutes a basic definition of selfhood, because a system has self-awareness, agency, and intents.

The FEP has been called everything from tautological, unfalsifiable, metaphorical, probably incomprehensible. Mark Solms calls it “the basic equation that explains your central aim and purpose in life, as well as that of everything that has ever lived.”

Which I somewhat object to. The FEP itself doesn’t explain as much as it tries to describe by analogy, and by describe it means to describe everything. It is ultimately drawn as an abstraction not a functional account of what the brain is actually doing, and it relies on a set of definitions that are tautological in a basic sense, ie if any thing exists in a state of lower entropy to stay in a state of lower entropy it needs to continue existing. It has been argued that the FEP then laboriously states the obvious and by explaining everything explains nothing, like saying that an organism has to not die in order to not die. In some sense, since the actual processes themselves require their own explanations, there is some extent to which the principle itself can basically be ignored.11

Nonetheless, the theory of affect that is drawn from it purports to explain all emotion and conscious experience as aspects of any self-organising system with degrees of evolved complexity, and thus to explain what consciousness is actually doing. Friston and Solms claim not just that this offers functional correlation to conscious experience but that under dual aspect monism it basically explains what it actually is. By reframing the hard problem, they argue that we can essentially dissolve it with such explanations and tear open the metaphysical veil between subject and object.

So can we? And importantly, if we have an explanation that grounds all conscious experience and desire in processes dependant on physical life within self-organising systems, and if the main feature of conscious experience is novelty and uncertainty, where does that leave arguments for an all-knowing God’s existence that rely on evoking the apparently transcendent nature of consciousness and its valences as certain absolute characteristics of that God?

Friston et al, The free energy principle made simpler but not too simple: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037015732300203X

Seth, Being You, 2021 (tbc - not referenced because Seth mocks but because he points out Friston has been parodied, for example by mock twitter accounts)

Actually according to the FEP basically any self-organising system that continues to exist.

Technically a ‘Markov Blanket’, an important term in the FEP that defines the statistical boundaries of a system through which it must infer the states of the external world.

Friston & Solms, How and why consciousness arises: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10057681/1/Friston_Paper.pdf

Solms, The hard problem of consciousness and the free energy principle: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02714/full#B78

ibid

ibid

Solms, The Hidden Spring, 2021

ibid

See: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/MArdnet7pwgALaeKs/why-i-m-not-into-the-free-energy-principle?utm_source=chatgpt.com

I haven't read part II yet, and it seems likely you will address this point, but:

To the extent that the FEP is meant to be a physicalist explanation for the arising of consciousness, I think it falls victim to one of the principal errors in physicalist philosophy of mind: a confusion of the contents of consciousness with consciousness itself.

Talk of self-regulation or self-observation as essential to a system's maintaining homeostasis is all well and good, but it's worth pointing out that a thermostat does this. And we need not invoke consciousness to explain the behavior of a thermostat (though of course panpsychists might do so). We can explain physical behavior—certainly the vast majority and maybe all of it—without reference to consciousness. But this also means that there is no way to simply point out behavior and somehow argue in the other direction, that such-and-such a behavior somehow causes consciousness.

And this difficulty is only exacerbated by the fact that any behavior we want to point to is itself only a phenomenon with, to, for, and/or as our own conscious experience itself: physical phenomena are only known to us as events within consciousness. And again, this brings us to the "hard" problem of consciousness, which FEP seems not only not to explain, but to simply ignore: note how the theory seems to begin by stating that all living systems already have "subjectivity" by their very nature. If "subjectivity" here is meant to refer to consciousness-as-such, then they have smuggled that in at the outset—begging the question. If, on the other hand, "subjectivity" here instead just means some kind of self-regulation, then it is nothing more than a sensor turned inwards, and this doesn't necessarily have anything to do with consciousness at all.

In short: there is no solution to the hard problem for physicalist philosophies of mind without explaining how a quantitative set of states can somehow generate qualitative states of phenomenal experience (note as well the casual reference to "qualitative" states in one of the quotes in Whiteley's piece—again, the FEP theorist here seems to smuggle in what needs to be proven or explained). FEP gets us no closer to such an account than any other physicalist theory of mind.

Interesting article, but does the theory explain why conscious perception would even need to emerge in the first place?